70% Size, 100% Accuracy: Lossless LLM Compression for Efficient GPU Inference via Dynamic-Length Float

- 1Rice University

- 2Case Western Reserve University

TL;DR: We introduce DFloat11, a lossless compression framework that shrinks BFloat16 models to roughly 70% of their original size without changing a single bit of their output. By exploiting the information inefficiency in how model weights are stored, DFloat11 uses Huffman coding on exponent bits and a custom GPU kernel for fast decompression during inference. This lets you run Llama 3.1 405B on a single 8-GPU node instead of two, decode 5.7–14.9× more tokens before hitting memory limits, and get 2.3–46× better throughput than offloading parts of the model to CPU.

The Problem: When "Close Enough" Isn't Good Enough

Large language models have gotten really good—and really big. A model like Llama 3.1 405B takes up 810 GB in BFloat16 format, which is more than what fits on a typical high-end GPU server with 8×80GB cards. This creates a simple but frustrating problem: you either need multiple expensive GPU nodes, or you need to compress the model somehow.

The standard solution is quantization: convert weights to lower precision (like 8-bit or 4-bit integers) to save memory. And for many tasks, it works fine. Benchmarks will tell you that 8-bit quantization causes "negligible" accuracy loss. But there's a catch: those benchmarks don't capture everything.

Here's what actually happens with quantization:

- Accuracy drops can be real: Quantizing DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Qwen-1.5B to 8-bit with SmoothQuant causes a 9.09% drop in reasoning task accuracy. That's not negligible.

- Outputs change in unexpected ways: Even when overall accuracy looks fine, individual answers flip from correct to incorrect (and vice versa). For instance, quantizing Qwen2-1.5B to 8-bit changes the correctness of 6.37% of answers on GSM8K—despite only a 0.3% accuracy drop.

- It's unpredictable: Whether quantization will hurt your specific use case depends on the model, the task, the quantization method, the bit-width, and probably the phase of the moon. You have to test everything yourself.

For applications where outputs need to match the original model exactly—think regulated industries, scientific computing, or just wanting your deployment to behave like the model you tested—this uncertainty is a deal-breaker.

The Insight: BFloat16 is Wasteful

Here's something interesting: BFloat16, the format used to store most modern LLM weights, is shockingly inefficient. Each BFloat16 number uses 16 bits split into three parts: 1 sign bit, 8 exponent bits, and 7 mantissa bits.

We measured the actual information content (Shannon entropy) of these components across various models. The sign and mantissa bits are well-utilized—their entropy is close to their bit-width. But the exponent? It carries only about 2.6 bits of actual information despite using 8 bits to store it.

Why? Because of how weights are distributed. Out of 256 possible exponent values, only about 40 ever show up. The rest never appear. And among those 40, the frequency distribution is extremely skewed—a few values are very common, and the rest are rare. This is a classic setup for compression.

The Solution: Dynamic-Length Float (DFloat11)

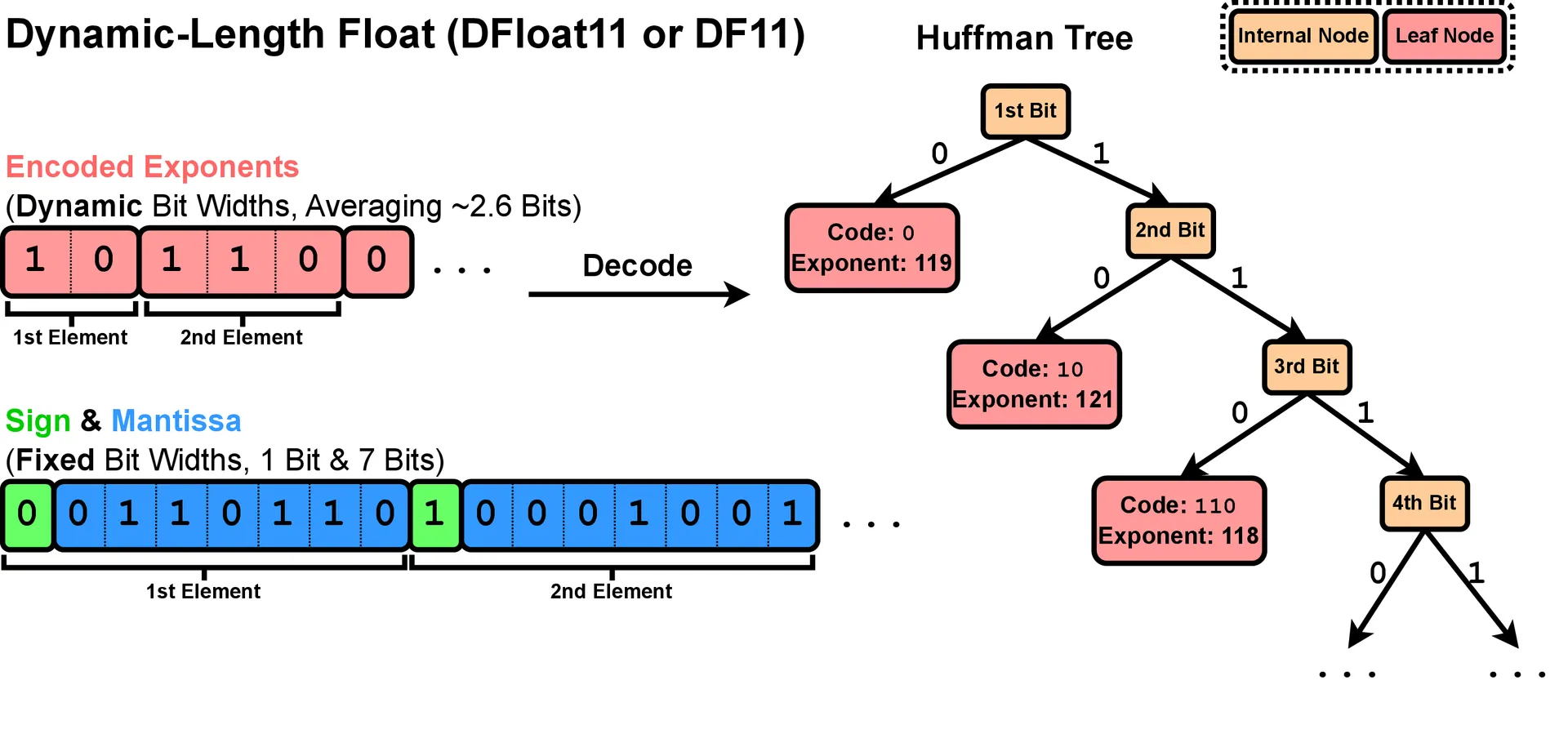

If frequent exponent values are common and rare ones are rare, we can encode them with variable-length codes: short codes for common values, longer codes for rare ones. That's exactly what Huffman coding does, and it's near-optimal for the frequency distribution we observe.

Our approach is simple:

- Build a Huffman tree from the exponent distribution across all model weights

- Encode exponents with dynamic-length codes (typically 2–32 bits instead of a fixed 8)

- Leave sign and mantissa bits uncompressed

- Pack everything tightly into memory

The result: weights that average around 11 bits instead of 16. That's roughly 30% smaller than the original BFloat16 model. And because we're just rearranging how the same information is stored—not throwing any away—decompressing gives you back the exact original bits. Bit for bit. No approximations, no accuracy loss, no behavioral changes.

The Challenge: GPUs Don't Like Variable-Length Anything

There's a reason this hasn't been done before. Huffman decoding is inherently sequential: you read bits one at a time, traverse a tree, decode a symbol, then repeat. This is terrible for GPUs, which are designed for massive parallelism. If you naively assign one thread to decode one value, you waste the GPU's potential and end up with high latency.

So we developed a custom GPU kernel that makes decompression fast enough for real-time inference. The key techniques:

1. Hierarchical Lookup Tables (LUTs)

Standard Huffman decoding would need a lookup table with entries (4.3 billion), which is far too big for GPU shared memory. Instead, we decompose the Huffman tree into four compact 256-entry tables that fit comfortably in GPU SRAM. We read one byte at a time and look it up in the first table. If the result is a reserved "continue" value, we read the next byte and check the second table, and so on. This gives us fast array lookups instead of sequential tree traversal.

2. Two-Phase Kernel Design

Because codes have variable length, figuring out where each thread should start reading is nontrivial. We use a gap array that stores the bit offset of the first valid code for each thread (5 bits per entry, since the maximum code length is 32 bits). For write positions, we use a two-phase approach: first, each thread decodes without writing to count how many symbols it produces; then threads synchronize within their block to compute output positions; finally, they decode again and write to the correct locations. This sounds wasteful, but the data stays in SRAM, so it's fast.

3. Transformer-Block-Level Batching

Decompressing a single small weight matrix underutilizes the GPU. But as matrix size grows, throughput improves (see Figure 3 in the paper). So instead of decompressing matrices one by one, we batch the decompression of all weight matrices in an entire transformer block. This maximizes GPU utilization and hides latency.

Results: Real Gains on Real Hardware

We tested DFloat11 on recent models including Llama 3.1/3.3, Qwen 3, Mistral 3, DeepSeek R1 Distilled, FLUX.1, and Stable Diffusion 3.5. Here's what we found:

Compression is consistent: Every model compressed to around 68–70% of its original size, with average bit-widths of 10.8–11.1 bits. For example:

- Llama 3.1 8B: 16.06 GB → 10.90 GB (67.84%)

- Llama 3.3 70B: 141.11 GB → 95.40 GB (67.61%)

- Llama 3.1 405B: 811.71 GB → 551.22 GB (67.91%)

- FLUX.1 dev: 23.80 GB → 16.33 GB (68.61%)

It's actually lossless: We verified this thoroughly. Accuracy on MMLU and TruthfulQA? Identical. Perplexity on WikiText and C4? Identical down to the decimal. We also checked that decompressed weights match the original on the bit level for every model. They do.

It enables bigger models on existing hardware: The headline result is that you can now run Llama 3.1 405B on a single node with 8×80GB A100 GPUs, instead of needing two nodes. That's cutting hardware requirements in half.

Throughput beats CPU offloading: When BFloat16 models are too big for GPU memory, the fallback is to offload parts to CPU. We compared this to DFloat11 (which fits entirely on GPU and decompresses on the fly). DFloat11 is 2.3–46× faster in terms of throughput or latency, depending on the model and batch size.

You can generate much longer sequences: During generation, the KV cache grows linearly with the number of tokens and quickly becomes a memory bottleneck. Because DFloat11 uses less memory for weights, more memory is available for the KV cache. This translates to 5.7–14.9× longer generation lengths before running out of memory.

Decompression overhead is small: At batch size 1, DFloat11 adds some latency compared to uncompressed BFloat16 (when both fit in memory). But as batch size increases, the constant decompression cost is amortized, and the gap shrinks. For diffusion models (Stable Diffusion 3.5, FLUX.1), decompression adds only 4–5.5% to generation time, while cutting memory usage by 28%.

It's faster than alternatives: We compared our kernel to CPU-to-GPU transfer (another strategy for memory-constrained settings) and to Nvidia's nvCOMP library (which offers ANS-based compression). DFloat11 achieves up to 34.95× higher throughput than CPU transfer and up to 20.97× faster decompression than nvCOMP. And unlike nvCOMP, our code is open source.

Why This Matters

Lossless compression hasn't gotten much attention in the LLM world because most prior work only helped with storage (like shrinking checkpoint files for download), not inference. DFloat11 is different—it's designed from the ground up for GPU inference.

This matters because:

- You avoid the guessing game of quantization: No need to test whether 8-bit will hurt your specific task on your specific model. If the BFloat16 model works, the DFloat11 version will behave identically.

- You get memory savings with performance benefits: Instead of trading memory for speed (as with CPU offloading or slow decompression), you actually get better throughput.

- You can deploy bigger models: That 405B model that needed two nodes? Now it fits on one.

- It's a building block for other techniques: Because DFloat11 is lossless, you can combine it with other methods (like KV cache quantization or speculative decoding) without worrying about compounding errors.

Technical Details

For those interested in the implementation:

The DFloat11 format stores exponents in a tightly bit-packed array EncodedExponent and keeps sign+mantissa bits in a separate array PackedSignMantissa. During inference, compressed weights live in GPU global memory. When a weight matrix is needed for a matrix multiplication, the decompression kernel reconstructs the BFloat16 matrix on the fly. After the matmul finishes, the decompressed matrix is discarded to save memory.

The kernel uses 256 threads per block, with each thread processing 8 bytes of encoded data. The number of blocks scales with matrix size. The hierarchical LUTs (four 256-entry tables) fit in shared memory. The gap array uses 5 bits per thread. The output position array uses 32 bits per block (not per thread), keeping overhead low.

Transformer-block-level batching means we decompress all weight matrices in a block (query, key, value, output, and MLP projections) together before running the forward pass. This improves utilization because larger batches make better use of GPU parallelism.

Limitations and Future Work

DFloat11 works well, but it's not a silver bullet:

- Decompression still costs something: At very small batch sizes or for tiny matrices, the overhead can be noticeable. This isn't an issue for standard LLM serving (where batch sizes are typically 4+), but it could matter for edge cases.

- It only compresses weights: The KV cache, which grows during generation, still uses the original format. Combining DFloat11 with KV cache compression could yield further gains.

- We focused on BFloat16 models: Most modern LLMs use BFloat16, but some use FP16 or other formats. The same principle (low exponent entropy) likely applies, but we haven't tested it.

Future directions include extending this to activations (not just weights), integrating with quantization-aware training pipelines, and exploring whether similar techniques apply to other model architectures (like transformers with different attention mechanisms).

Abstract

Large-scale AI models, such as Large Language Models (LLMs) and Diffusion Models (DMs), have grown rapidly in size, creating significant challenges for efficient deployment on resource-constrained hardware. In this paper, we introduce Dynamic-Length Float (DFloat11), a lossless compression framework that reduces LLM and DM size by 30% while preserving outputs that are bit-for-bit identical to the original model. DFloat11 is motivated by the low entropy in the BFloat16 weight representation of LLMs, which reveals significant inefficiency in the existing storage format. By applying entropy coding, DFloat11 assigns dynamic-length encodings to weights based on frequency, achieving near information-optimal compression without any loss of precision.

To facilitate efficient inference with dynamic-length encodings, we develop a custom GPU kernel for fast online decompression. Our design incorporates the following: (i) compact, hierarchical lookup tables (LUTs) that fit within GPU SRAM for efficient decoding, (ii) a two-phase GPU kernel for coordinating thread read/write positions using lightweight auxiliary variables, and (iii) transformer-block-level decompression to minimize latency.

Experiments on Llama 3.3, Qwen 3, Mistral 3, FLUX.1, and others validate our hypothesis that DFloat11 achieves around 30% model size reduction while preserving bit-for-bit identical outputs. Compared to a potential alternative of offloading parts of an uncompressed model to the CPU to meet memory constraints, DFloat11 achieves 2.3–46.2× higher throughput in token generation. With a fixed GPU memory budget, DFloat11 enables 5.7–14.9× longer generation lengths than uncompressed models. Notably, our method enables lossless inference of Llama 3.1 405B, an 810GB model, on a single node equipped with 8×80GB GPUs. Our code is available at https://github.com/LeanModels/DFloat11.