Don’t Pass@𝑘: A Bayesian Framework for Large Language Model Evaluation

- 1Department of Computer and Data Sciences, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH, USA

- 2Department of Physics, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH, USA

TL;DR: Replace Pass@k with a posterior-based protocol (Bayes@N) that (i) yields stable, faster-converging rankings, (ii) provides credible intervals and a clear decision rule, and (iii) naturally unifies binary and graded evaluation; avg@N can be reported alongside since it’s rank-equivalent under a uniform prior.

Story behind

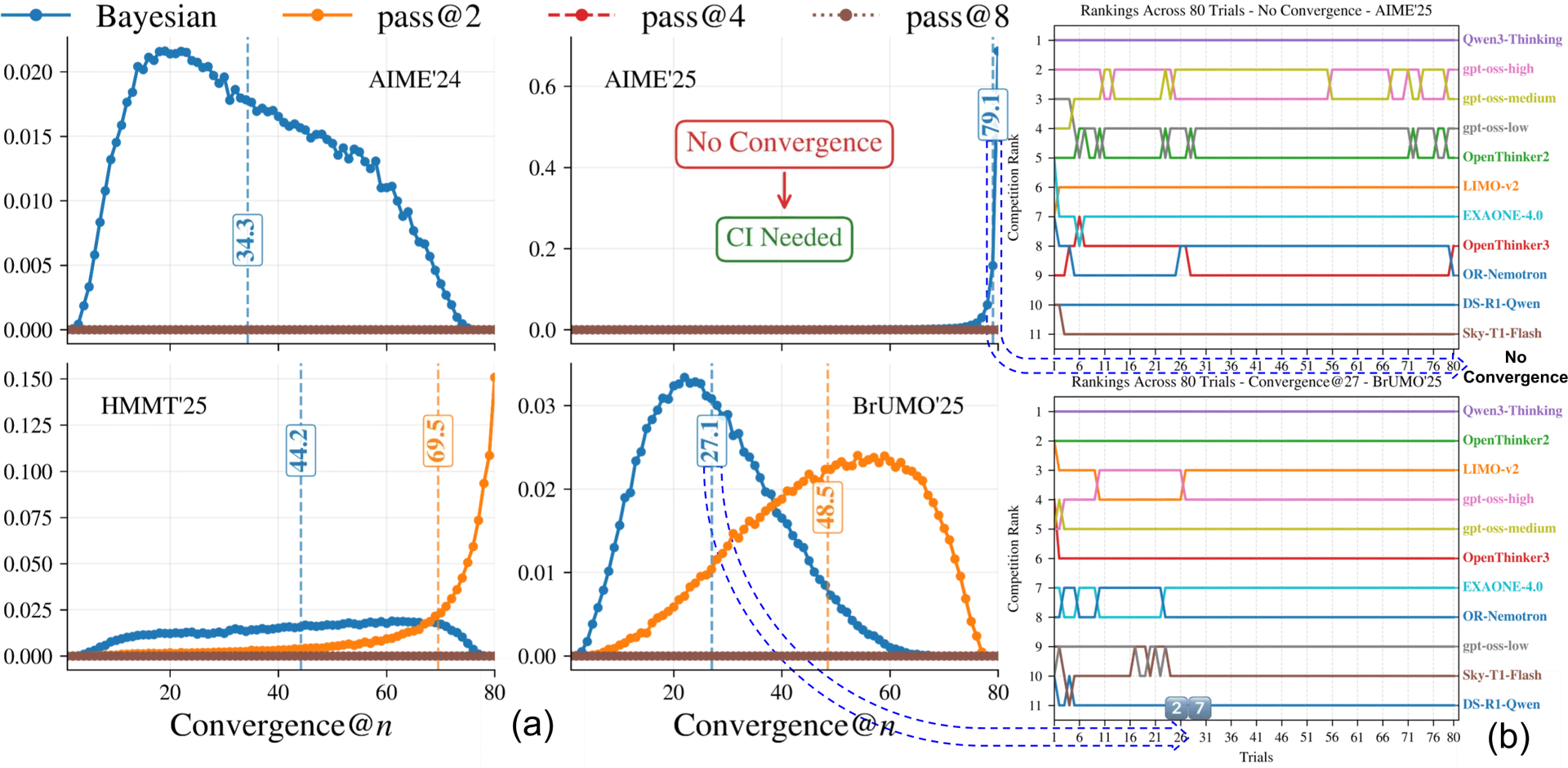

We were benchmarking reasoning models (e.g., DeepSeek-R1, Qwen-thinking) and kept circling the same deceptively simple question: how many trials are enough? With no oracle to consult, we took 11 models from different families (DeepSeek-distilled, Qwen, Microsoft, Nvidia, etc.), ran 8 trials, and noted the ranking, then out of curiosity ran one more, and the leaderboard changed. At 16 trials it flipped again. We pushed all the way to N = 80, and even there AIME’25 refused to settle into a truly stable ordering. That instability pushed us to study the problem systematically (including simulations): (i) since we use non-deterministic decoding (e.g., top_p), how many trials are actually required and if an oracle told us the right N, which evaluation metric best estimates the model’s true performance? This paper is the answer to those questions.

How to use in practice?

We release scorio, which can be installed via pip using pip install scorio, or in Julia with pkg> add Scorio. In addition to Bayes@N, scorio supports many evaluation metrics, including avg@N, Pass@k, Pass^k, G-Pass@k, and mG-Pass@k. The source code and documentation are available at https://mohsenhariri.github.io/scorio.

Consider a dataset with questions. An LLM is used to generate independent trials (samples) per question and evaluate each trial using a rubric that assigns it to one of categories: . The results are stored in an matrix , where denotes the category of the -th trial for question . Optionally, you may include prior runs in a matrix with trials per question.

The simplest and most common rubric is binary (), where each trial is either correct (1) or incorrect (0). In this case, the results matrix contains only 0s and 1s. Suppose the dataset has questions and you run trials per question, resulting in an matrix . See the example below:

from scorio import eval

w = [0, 1] # 0 for incorrect, 1 for correct

mu, sigma = bayes(R, w)

# if you have prior runs, let's say you run N top_p sampling and one greedy decoding (R0)

mu, sigma = bayes(R, w, R0)using Scorio

w = [0, 1]

mu, sigma = bayes(R, w)Abstract

Pass@k is widely used to report performance for LLM reasoning, but it often yields unstable and misleading rankings, especially when the number of trials (samples) is limited and compute is constrained. We present a principled Bayesian evaluation framework that replaces Pass@k and average accuracy over N trials with posterior estimates of a model's underlying success probability and credible intervals, yielding stable rankings and a transparent decision rule for differences. Evaluation outcomes are modeled as categorical (not just 0/1) with a Dirichlet prior, giving closed-form expressions for the posterior mean and uncertainty of any weighted rubric and enabling the use of prior evidence when appropriate. Theoretically, under a uniform prior, the Bayesian posterior mean is order-equivalent to average accuracy (Pass@1), explaining its empirical robustness while adding principled uncertainty. Empirically, in simulations with known ground-truth success rates and on AIME’24/’25, HMMT’25, and BrUMO’25, the Bayesian/avg procedure achieves faster convergence and greater rank stability than Pass@k and recent variants, enabling reliable comparisons at far smaller sample counts. The framework clarifies when observed gaps are statistically meaningful (non-overlapping credible intervals) versus noise, and it naturally extends to graded, rubric-based evaluations. Together, these results recommend replacing Pass@k for LLM evaluation and ranking with a posterior-based, compute-efficient protocol that unifies binary and non-binary evaluation while making uncertainty explicit. Source code is available at https://mohsenhariri.github.io/scorio.

How to evaluate the evaluation metrics?

We start by fixing a gold standard ranking using a large trial budget. We then take each evaluation metric such as avg@, Pass@, and its variants, compute its ranking at smaller where (or in the case of the Pass@ family), and compare it to the gold standard using Kendall’s across bootstrap replicates. In our experiments on AIME’24 and AIME’25, HMMT’25, and BrUMO’25, Bayes@ and thus avg@ climbs to higher faster and reaches a better plateau than Pass@ style methods, which reflects quicker and more stable agreement with the reference.

We make uncertainty explicit with credible intervals and a clear decision rule, approximate the posterior for as normal, compare two models with the score

and map to a ranking confidence

We only call a winner when credible intervals do not overlap or when exceeds a preset threshold, for example for approximately .

Finally, we report convergence@, the smallest after which a method’s ranking matches the gold standard and stays fixed, estimating its distribution via bootstrap. Practically, we summarize this with convergence() PMFs and CDFs. On the math reasoning benchmarks above, Bayes@ converges reliably with fewer trials than Pass@ variants, which sometimes never settle. A lower mean convergence@ indicates a more compute efficient evaluation metric.

Why Pass@k is Problematic?

Pass@ produces high variance and unstable rankings at small evaluation budgets, leading to noisy comparisons between models. It also struggles with quantifying uncertainty, since estimating confidence requires bootstrapping, which becomes unreliable when is small. In practice, Pass@ converges more slowly to the true model ranking and often fails to stabilize within a reasonable trial budget, unlike Bayes@ or avg@. Moreover, Pass@ reduces outcomes to a simple “any success” criterion, making it unsuitable for graded or rubric-based evaluations, which are crucial for reasoning and RL-fine-tuned models where partial or categorical correctness matters.

Simulation

Try out the interactive demo below.

Algorithm

In principle, we could estimate by running an arbitrarily large number of trials with the LLM, yielding an accurate estimate of . However, we are typically constrained to small due to limited computational resources. Our goal is to develop a Bayesian approach to estimate and its associated uncertainty given a finite .

The first step is to construct the posterior distribution

the probability of given the -th row of the matrix , denoted . This posterior depends on the observed data and a chosen prior distribution for the unknown underlying probability vector . The prior could be uniform (assuming no prior information) or incorporate previously gathered evidence about the LLM's performance.

The Bayesian framework focuses on two key quantities:

Posterior mean of , denoted , which is the mean of over the joint posterior for all questions:

This is the Bayesian optimal estimator, minimizing the quadratic loss function

over all possible estimators , where the expectation is taken over all possible and realizations of .

Posterior variance, denoted , which quantifies the uncertainty of the estimate:

Both and have exact closed-form expressions, derived in Appendix A of the paper, and can be efficiently computed for any using the Algorithm below.